This was not a ceremonial groundbreaking. That happened months ago. This was a progress assessment—the bureaucratic phrase that barely captures what unfolded over four hours of site inspection and consultative meetings.

The verdict, delivered jointly and without equivocation: the MMU Affordable Student Village Project is not merely on schedule. It is, by multiple indicators, ahead of it.

THE NUMBERS: 2,500 Beds, Three Blocks, One Vision

Let the arithmetic speak first.

Three modern hostel blocks. Total capacity: 2,500 students. Completion timeline: on or before schedule, according to Ndambuki, who did not hedge when pressed by reporters on site .

But capacity is only half the equation. The other half—the revolutionary half—lies in what these blocks contain that no comparable student housing in Kenya's public university system has ever mandated as standard.

An underground water tank of unspecified but substantial capacity, designed to render the student village entirely immune to Nairobi Water's intermittent supply whims. A ground-floor ramp system that does not treat accessibility as an afterthought bolted onto an able-bodied design, but as a fundamental circulation principle embedded from the first foundation pour. And crucially, a lift—not a freight elevator for maintenance staff, but a passenger lift intended for daily use by all students, including those with mobility disabilities who have historically been relegated to ground-floor rooms or, worse, denied on-campus accommodation entirely .

"Accessibility considerations have been incorporated," Ndambuki said, understating what is arguably the most progressive accessibility mandate ever applied to Kenyan public university housing .

THE POLITICS: Why Ruto's Affordable Housing Programme Came to MMU

The project does not exist in a political vacuum.

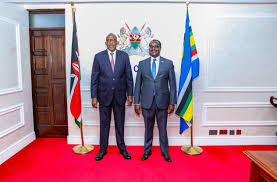

Prof. Maranga, in her remarks, was unequivocal in her gratitude. "We thank the President for this project," she said, naming H.E. William Ruto directly—a deliberate acknowledgment that MMU's selection was not arbitrary but strategic .

The Affordable Housing Programme, Ruto's signature infrastructure initiative, has extended its reach beyond the low-income urban estates for which it was originally conceived. Universities, it turns out, are the programme's next frontier. And MMU, nestled along the Magadi Road corridor, is its flagship higher education beneficiary.

Dr. Kochei framed the project in governance terms: "strong governance in the successful implementation of the project," he said, and "strategic oversight" to ensure alignment with the university's long-term development goals .

The translation, stripped of bureaucratic cadence: this project will not fail. Not on Kochei's watch. Not with the President's name attached.

THE SITE VISIT: Hard Hats, Muddy Boots, and a Contractor Ahead of Schedule

The consultative meeting occupied the morning's first hour. Conference room, PowerPoint slides, procurement updates, cash flow projections. Necessary bureaucracy.

Then the hard hats were distributed, and the delegations walked into the site.

What they found surprised even the optimists.

The contractor, whose identity remains undisclosed in official communications, has mobilised resources at a velocity uncommon in Kenya's public works sector. Steel reinforcements are stacked in orderly rows. Concrete mixing occurs on-site under quality control supervision. The lift shafts, among the most technically demanding elements of the construction, are visibly progressing.

Ndambuki, surveying the scene, delivered what may be the understatement of the inspection tour: "The contractor is already ahead of schedule" .

Multimedia University's current on-campus accommodation capacity is not publicly advertised. The university, like most Kenyan public institutions, has historically operated a housing deficit that forced thousands of students into the private rental markets of Rongai, Ongata Rongai, and the Kiserian sprawl.

"Research shows that learners perform better academically, have higher morale, and enjoy improved overall well-being when they are in a safe, supportive and conducive environment," she said .

THE INCLUSION MANDATE: Ramps, Lifts, and the Unnamed Students

Here is what the official photographs do not show.

They do not show the student in a wheelchair who currently commutes daily from Rongai because MMU's existing hostels—constructed in an era before disability mainstreaming—cannot accommodate her. They do not show the visually impaired undergraduate who navigates staircases by counting steps, a system that fails when maintenance workers relocate furniture to corridors.

But the new village sees them.

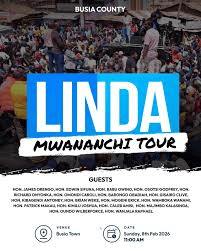

A new modern library, implemented in collaboration with the Ministry of Works, is progressing. The paved footpath from MMU to Rongai Town, delivered by KeNHA, has already improved safety for thousands of pedestrians. The Kenya-Korea Information Access Center, supported by the Government of South Korea, continues to expand its ICT training capacity .

And now, the Student Village.

Taken together, these projects constitute a capital transformation unprecedented in MMU's history. The university that began as a training ground for Kenya Broadcasting Corporation technicians has, in less than three decades, accumulated the physical infrastructure of a comprehensive technological university.

THE GUARANTEE: 'Completed on Schedule and to Required Standards'

The joint communiqué, delivered informally at the conclusion of the site visit, carried the weight of a contractual undertaking.

The phrasing is careful. "On schedule" acknowledges the contractor's current momentum. "Required standards" invokes the full apparatus of government quality assurance, from National Construction Authority inspections to National Environment Management Authority compliance.

This is not a project that will be permitted to stall, to suffer cost overruns, to become another half-finished skeleton in Kenya's public works graveyard.

The political optics alone preclude failure.

THE VERDICT: More Than Bricks

As the delegations removed their hard hats and retreated to the university boardroom for refreshments, a construction supervisor remained on-site, shouting instructions to a crane operator.

The beam swung slowly, gracefully, settling into position atop the third block's rising frame.

Dr. Kochei had spoken earlier of "transformative" impact. Prof. Maranga had invoked student "well-being." Ndambuki had pledged "fast-track" execution.

But the beam, settling into its bed of wet concrete, spoke loudest.

It said: 2,500 students will sleep safely here.

It said: the student in a wheelchair will no longer commute.

It said: this government programme, whatever its political origins, is delivering tangible infrastructure that changes lives.

The MMU Affordable Student Village Project is not yet complete. Scaffolding remains. Finishing works await. The underground water tank has not yet collected its first drop.

But on a Thursday morning in late January 2026, two delegations walked through mud and steel and rising concrete, and they agreed on what they saw.

Progress.

Steady, measurable, on-schedule, up-to-standard progress.

For 2,500 students—named and unnamed, present and future, able-bodied and disabled—that progress cannot come soon enough.

WHAT COMES NEXT

They will test the lift. They will draw water from the underground tank. They will occupy a student village built not merely to house them, but to include them.