The echoing halls of Parliament Buildings in Nairobi, where the scent of polished mahogany mingles with the urgency of legislative drafts, witnessed a bold gambit on the afternoon of November 10, 2025, as Laikipia Woman Representative Jane Kagiri rose during the First Reading to table a bill that could reshape the corporate landscape of Kenya's burgeoning economy. The Employment (Amendment) Bill, 2025, sponsored by the United Democratic Alliance lawmaker, seeks to impose a stringent cap: no more than 20 percent of staff in multinational firms operating within Kenya may be foreign nationals, with a mandatory 80 percent reserved for Kenyan citizens—a quota extending even to the rarified air of top management suites. "This is not protectionism; it is patriotism—a deliberate pivot to prioritize our youth, our graduates, our untapped talent pool that watches opportunities slip to expatriates while unemployment festers," Kagiri declared from the dispatch box, her voice cutting through the chamber's murmurs as she gestured to stacks of supporting memos from Laikipia ranchers and Nairobi tech hubs alike. "For too long, we've hosted giants who extract value but export jobs. This bill ensures that at least eight in every ten positions—from the factory floor to the corner office—are filled by Kenyans, fostering skills transfer, wealth retention, and the dignity of work on our soil."

Kagiri's proposal, a 28-page document now slated for public participation hearings starting November 20 under the stewardship of the National Assembly's Labour Committee, arrives amid a crescendo of public discontent over the perceived expatriate stranglehold on lucrative roles in sectors like technology, finance, manufacturing, and extractives. Multinationals—behemoths such as Google Africa in Nairobi's Upper Hill, Safaricom's international partnerships, Unilever's East African hub in Kericho, or the Chinese-funded Standard Gauge Railway operations—employ over 500,000 Kenyans directly, yet audits by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics reveal that foreign nationals occupy 35 percent of senior management positions and 25 percent overall, often on salaries triple the local equivalents. "We've seen Indian CEOs in tea factories where Kenyan agronomists toil below, European CFOs in banks where our accountants crunch numbers, Chinese engineers on infrastructure projects sidelining our graduates," Kagiri elaborated in a post-tabling briefing at Parliament's media center, her Laikipia shuka draped like a banner of rural resolve. "The bill mandates 80 percent Kenyanization across the board—entry-level to executive—with phased compliance over three years for existing firms and immediate for new entrants. Non-compliance? Fines starting at Sh10 million, escalating to license revocation."

The bill's genesis traces to Kagiri's constituency travails in Laikipia, a sprawling county of vast ranches, geothermal fields, and conservation hubs where multinational agribusinesses like Del Monte and floral giants such as Oserian employ thousands yet import managers from Europe and Asia. During a September 2025 baraza at Rumuruti's dusty market grounds, 200 youth—graduates in engineering and business studies idling with boda bodas—confronted the MP with placards reading "Jobs for Kenyans, Not Expats." "Madam, we've degrees from JKUAT, but the Dutch run the flower farms while we prune roses for Sh500 a day," vented 28-year-old mechanical engineer Peter Nderitu, his diploma clutched like a talisman. Kagiri, a former corporate HR executive who flipped Laikipia from ODM to UDA in 2022 on a platform of economic empowerment, took the plea to heart, commissioning a county survey that found 42 percent of managerial roles in Laikipia's 15 multinationals held by foreigners. "Laikipia mirrors Kenya—rich in land, richer in talent, yet starved of opportunity," she reflected in her bill's memorandum, citing World Bank data showing Kenya's youth unemployment at 13 percent while 60,000 skilled expatriates hold work permits renewed annually.

The legislation's teeth lie in its comprehensive scope and enforcement mechanisms. Clause 4 amends the Employment Act, 2007, to define "multinational firm" as any entity with foreign equity exceeding 30 percent or annual turnover above Sh5 billion, compelling them to submit annual "Kenyanization plans" to the Ministry of Labour, audited by the National Employment Authority. Top management—CEO, CFO, CTO, and equivalents—must achieve 80 percent localization within five years, with interim targets of 50 percent by year three. Skills transfer mandates require foreign hires to mentor two Kenyan understudies, with tax incentives—up to 15 percent corporate relief—for firms exceeding quotas. "This isn't expulsion; it's elevation—expats bring expertise, but must bequeath it," Kagiri emphasized, pointing to Rwanda's 2023 model where 70 percent localization in telecoms spurred 20,000 local promotions. Penalties escalate: Sh5 million for first offenses, Sh20 million and permit cancellations for repeats, with a whistleblower fund rewarding tips on violations.

Reactions cascaded like a Rift Valley waterfall, splitting along ideological and sectoral lines. In Nairobi's Silicon Savannah, where Google, Microsoft, and IBM hubs employ 5,000, tech CEOs convened an emergency roundtable at the Radisson Blu. "This risks innovation flight—top talent is global; capping it caps growth," warned Google Africa's country director Agnes Gathaiya in a statement, her words echoing fears of 10 percent staff cuts if expatriate AI specialists depart. Safaricom CEO Peter Ndegwa, whose firm boasts 85 percent Kenyan staff but relies on 15 percent foreign expertise in cybersecurity, urged dialogue: "We support localization—95 percent of our engineers are local—but mandating C-suite quotas could deter FDI; let's phase wisely." The Kenya Private Sector Alliance, representing 300 multinationals, petitioned for exemptions in "critical skills" like deep-sea oil drilling, where Kenyan expertise lags. "80 percent is ambitious; 60 percent realistic—train, don't truncate," KEPSA chair Jaswinder Bedi lobbied during a November 10 meeting with Kagiri, his delegation armed with charts showing Sh1.2 trillion in annual multinational investments at risk.

Yet, support swelled from labor and youth quarters. The Central Organization of Trade Unions, led by Francis Atwoli, endorsed the bill at a Kisumu rally: "Finally, a law with bite—expats have feasted; time for Kenyans to feast," Atwoli thundered to 2,000 workers. The Kenya Young Parliamentarians Association, with 50 MPs under 35, co-sponsored amendments for internship quotas. "This is Gen Z's jobs bill—our degrees gather dust while visas fly in talent," declared Kisumu West MP Rosa Buyu, her motion drawing bipartisan cheers. In Laikipia, Nderitu's boda crew mobilized 500 signatures: "Kagiri delivers—80 percent means my wrench turns gears, not waits." Rural counties like Kericho, where Unilever's tea operations employ 10,000, saw PTA chairs hail it: "British managers earn Sh2 million; Kenyan assistants Sh80,000—level the leaf," quipped a Kericho farmer at a November 11 baraza.

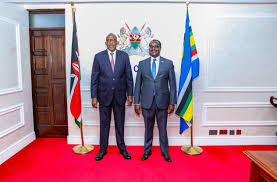

The bill's path winds through public hearings—Nairobi on November 25, Mombasa December 2, Eldoret December 5—with the Labour Committee chaired by UDA's Mwangi Kiunjuri poised to mediate. "We'll balance patriotism with pragmatism—exemptions for rare skills, incentives for training," Kiunjuri assured in a committee briefing, his nod to Kagiri a signal of ruling party backing. President Ruto, whose "Bottom-Up" mantra aligns with localization, previewed support in a November 9 Laikipia tour: "Kenyans first—in factories, farms, and boardrooms." Opposition from Azimio, led by ODM's John Mbadi, critiqued enforcement: "Good intent, but without training funds, it's hollow—pair with Sh50 billion skills fund."

For multinationals, compliance looms large: Google's 200 foreign staff must shrink to 40; Safaricom's 300 to 60. "We'll upskill—promote locals, mentor aggressively," Ndegwa pledged, announcing Sh500 million for Kenyan tech academies. In Laikipia, Del Monte's Dutch GM eyes succession: "Train the deputy; transition in three years." Youth like Nderitu dream big: "From boda to boardroom—Kagiri's bill is my visa." As Parliament adjourns for hearings, the 80-20 equation hangs in balance: patriotism's promise or investment's peril. Kagiri, undeterred, rallies: "Kenya hosts; Kenyans helm—80 percent isn't cap; it's crown."

The bill's clauses detail phased rollout: Year 1, 50 percent localization in mid-management; Year 3, 80 percent overall; Year 5, C-suite compliance. Tax breaks for firms hitting 90 percent, grants for training 1,000 locals yearly. Public participation portals launch November 15, targeting 100,000 submissions. KEPSA's Bedi pushes amendments: "Critical skills list—AI, biotech exempt." COTU's Atwoli counters: "No exemptions; train or transfer." Ruto's PS for Labour, in a memo, aligns with Kagiri: "FDI with face—Kenyan face." In boardrooms and barazas, the debate rages: 80 percent empowerment or exodus. Nderitu's wrench gleams: "My turn now."