The rolling plains of eastern Uganda, where the acacia-dotted savannas stretch toward the Kenyan border like an unspoken invitation to shared destinies, have long served as a backdrop for diplomatic dances that blend brotherly banter with the undercurrents of hard-nosed negotiation. On November 10, 2025, during a candid radio interview at Mbale State Lodge in the shadow of Mount Elgon—a dormant volcano straddling the two nations' frontiers—Uganda's President Yoweri Museveni dropped a statement that sent ripples across the East African Community, warning that future wars could erupt between Uganda and Kenya if the latter treats Uganda's access to the Indian Ocean as a "privilege" rather than an inalienable right. Speaking with the measured gravitas of a leader who has steered his country through decades of turmoil, Museveni decried the "madness" of blocking landlocked nations from sea routes, insisting that Uganda's economic vitality and security imperatives entitle it to unfettered passage through Kenyan ports like Mombasa. "Uganda is landlocked inside here. But where is my ocean? My ocean is the Indian Ocean. It belongs to me," Museveni asserted, his voice rising with the fervor of a man invoking ancestral claims. "I am on the top floor of the block, and then you say the compound belongs only to the ones on the ground floor. This is madness. Blocking landlocked countries from access to the sea is not just unfair; it endangers everyone."

Museveni's remarks, broadcast live on a popular Mbale radio station and later dissected in headlines from Kampala to Nairobi, came amid a backdrop of longstanding frictions over trade infrastructure that have periodically strained the fraternal ties between the two neighbors. Uganda, a landlocked powerhouse of 48 million souls nestled between the Great Lakes and the Rwenzori Mountains, relies on Kenya's Mombasa port for 90 percent of its imports and exports, funneling everything from petroleum worth Sh200 billion annually to fertilizer sacks that sustain its coffee and maize belts. The relationship, forged in the fires of colonial legacies and post-independence solidarity, has weathered storms: the 1970s border closures under Idi Amin's erratic rule, the 1980s refugee flows during Museveni's bush war, and more recent spats over the 2018 Standard Gauge Railway fares that saw Ugandan cargo rates hike 20 percent, costing Kampala Sh50 billion in extra levies. Yet, Museveni framed the current unease not as malice but as myopia, a failure of vision that could ignite conflicts if left unaddressed. "That is why we have endless discussions with Kenya—then this one stops, another one comes. The railway, the pipeline, the water—we discuss. But that ocean belongs to me because where is my ocean?" he elaborated, his tone a mix of exasperation and exhortation, gesturing as if mapping invisible seaways on the lodge's teak table.

At the heart of Museveni's plea lies a profound vulnerability for Uganda: its geographical isolation, a colonial cartographer's caprice that denies it direct maritime access while encircling it with neighbors whose ports it must navigate like a supplicant at a feast. Landlocked since the 1962 independence, Uganda's economy—valued at $50 billion and growing at 6 percent annually—hinges on the 1,200-kilometer haul from Mombasa to Kampala, a corridor plagued by delays at Malaba border posts and bottlenecks at the port where Kenyan customs agents process 18 million tons of Ugandan-bound cargo yearly. Museveni, drawing from his military strategist roots honed during the 1981-1986 liberation war, highlighted the security peril: "In Uganda, even if you want to build a navy, how can you build it? You have no ocean." This rhetorical flourish underscores a deeper anxiety—Uganda's nascent marine unit, the Uganda People's Defence Forces' Naval Wing, trains on Lake Victoria's choppy waters but lacks blue-water capabilities, rendering it impotent against threats like Somali piracy or potential Red Sea disruptions. "We are entitled to that ocean for economic and security needs," Museveni pressed, his words a clarion call for reciprocity in the East African Community, where the 1999 Protocol on the Free Movement of Goods envisions seamless trade but stumbles on port privileges.

Museveni's frustration is not abstract; it is etched in the annals of bilateral haggling that have defined Kenya-Uganda relations for generations. The two nations, bound by 933 kilometers of shared border and a history of mutual aid—from Uganda hosting 200,000 Kenyan refugees during the 2007 post-election violence to Kenya absorbing Ugandan exports worth Sh400 billion annually—have navigated flashpoints with a blend of pragmatism and pique. The 1978-1979 rift, when Amin's tanks rolled toward the Kenyan frontier amid oil price wars, closed borders for months, crippling Uganda's tea trade. More recently, the 2022 oil pipeline standoff saw Museveni accuse Nairobi of "unfriendly tariffs," delaying the $3.5 billion East African Crude Oil Pipeline that would snake 1,443 kilometers from Turkana to Tanga, bypassing Mombasa. "We discuss, but progress is piecemeal—the ocean should be a right, not a negotiation," Museveni lamented, his interview a veiled prod at ongoing talks for a Sh150 billion port expansion deal that would allocate Uganda dedicated berths in exchange for 30-year usage rights. Kenyan Foreign Affairs PS Korir Sing'oei, responding in a November 11 statement from State House, struck a conciliatory note: "President Museveni is our elder brother; his concerns are ours. Kenya-Uganda trade is symbiotic—Sh500 billion in bilateral flows last year—and we commit to equitable access, as per EAC protocols."

The two countries' tapestry of ties, woven from colonial threads and post-independence pacts, is a rich brocade of cooperation laced with occasional fraying. Sharing not just borders but bloodlines—intermarriages blending Luo and Baganda communities, families straddling the Malaba River like it were a garden fence—Kenya and Uganda have co-authored milestones: the 1999 EAC revival, the 2000 tripartite customs union with Tanzania, and the 2023 joint anti-terror drills along the Lake Victoria basin. Trade, the lifeblood, pulses at Sh1 trillion annually: Uganda's matooke and coffee flood Nairobi markets, Kenya's petroleum and machinery sustain Kampala's factories. Yet, disagreements simmer like embers under ash: the 2024 maize export bans during Kenya's drought sparked Ugandan farmer protests, while Uganda's 2023 gold smuggling ring through Busia cost Kenya Sh20 billion in lost revenue. Museveni, ever the pan-Africanist whose 1986 bush war victory birthed the no-party system he has ruled for 39 years, invokes history's lessons. "Africa's borders are irrational—drawn by pencils in Berlin, ignoring our rivers and migrations," he reflected, his words a echo of his 2017 AU address calling for continental federation. "Unity is the antidote to war; let us share the ocean as siblings, not sue for it as strangers."

Museveni's navy lament, a poignant aside in the interview, reveals the strategic chasm landlocked status carves. Uganda's marine aspirations, sketched in the 2021 Defence White Paper, envision a blue-water force to patrol Lake Albert's oil fields and counter Al-Shabaab incursions from Somalia's coast. Yet, without ocean access, the UPDF's flotilla—six patrol boats on Victoria, two gunboats on Albert—remains pond-bound, reliant on Kenyan berths for training and Tanzanian ports for overhauls. "How can a nation defend its flanks without a flank to the sea?" Museveni posed, his metaphor of the condominium block—a top-floor tenant denied the courtyard—striking a chord with landlocked brethren like Rwanda and Burundi, who nodded in virtual solidarity via EAC channels. Kenyan Defence CS Aden Duale, in a November 11 retort from the Pentagon during a bilateral security meet, extended an olive branch: "Uganda's security is Kenya's shield—joint naval drills in Mombasa, shared intel on Indian Ocean threats. The sea is not ours alone; it's East Africa's artery."

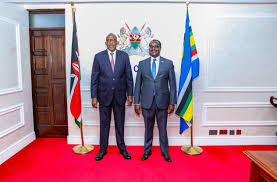

The interview's timing, just weeks before the EAC Summit in Arusha on December 5, amplifies its diplomatic decibels. Museveni, whose NRM has dominated Ugandan politics since 1986 amid accusations of authoritarian drift, uses such platforms to burnish his elder statesman credentials, his 2026 re-election bid shadowed by opposition cries from Bobi Wine. Ruto, Kenya's 2022 victor whose "Bottom-Up" mantra echoes Museveni's pan-Africanism, responded with warmth: "President Museveni is our guiding light; Kenya's ports are Uganda's gateways—let's deepen the dialogue, not divide the dream," he stated in a November 12 address at the Nairobi International Convention Centre, where 500 EAC envoys gathered for a trade expo. The duo's rapport, forged in the 2022 election's mutual endorsements, has weathered tests: the 2024 border spat over gold smuggling, resolved with joint patrols, and the 2023 refugee row when Uganda hosted 50,000 Kenyans fleeing floods.

For ordinary citizens straddling the border—Luo traders in Busia hawking fish from Victoria, Baganda mechanics in Malaba tuning Kenyan lorries—the rhetoric resonates as reality. "Museveni talks ocean rights; I talk daily bread—Sh2,000 tolls to Mombasa eat my profits," grumbled 45-year-old trucker Mary Atieno from Kisumu, her lorry idling at Malaba's customs queue where delays stretch to 48 hours. In Kampala's Owino Market, Ugandan vendor John Okello echoed the plea: "Kenya's port is our pulse—block it, and our hearts stop." The EAC's 2025 customs union review, slated for Arusha, could forge fixes: dedicated Ugandan lanes at Mombasa, digital single windows slashing clearance to 24 hours, and joint revenue-sharing on transit fees worth Sh100 billion yearly.

Museveni's warning, far from saber-rattling, is a statesman’s siren: a call to transcend borders drawn by distant drafters, to weave economies into unbreakable webs. "Wars are won in council chambers, not combat zones—let us choose the ocean as ally, not adversary," he concluded, his interview a bridge over troubled tides. As November's Nile winds whisper across the frontier, Kenya and Uganda stand at the estuary: ports as pacts, seas as siblings—a shared horizon where madness yields to maritime mateship.

Museveni's interview, aired on Mbale's Vision FM, drew 1.2 million listeners, its clips trending on X with #OceanRightsEA amassing 50,000 posts. Ruto's response, at the NICC expo, pledged Sh20 billion for Malaba upgrades, drawing applause from 200 Ugandan traders. EAC Secretary General Peter Mathuki hailed it as "timely candor," convening a November 15 virtual huddle for port protocols. For Atieno and Okello, the talk translates to trucks: faster clearances mean Sh5,000 daily savings, bread on tables from Busia to Bombo. In the EAC's evolving epic, where borders blur into brotherhood, Museveni's words endure as wake-up: access not as alms, but as axiom—a right rippling from Mombasa to the mountains, where two nations navigate not as neighbors, but as one.